From Distance: Lessons from Psychohistory

2018-02-22

Note: As it has been a quiet week in the NBA, I thought I’d try something different. I invite you to read the following with different glasses. Try reading it while thinking of team draft/tanking approach, or politically, or simply about relationships.

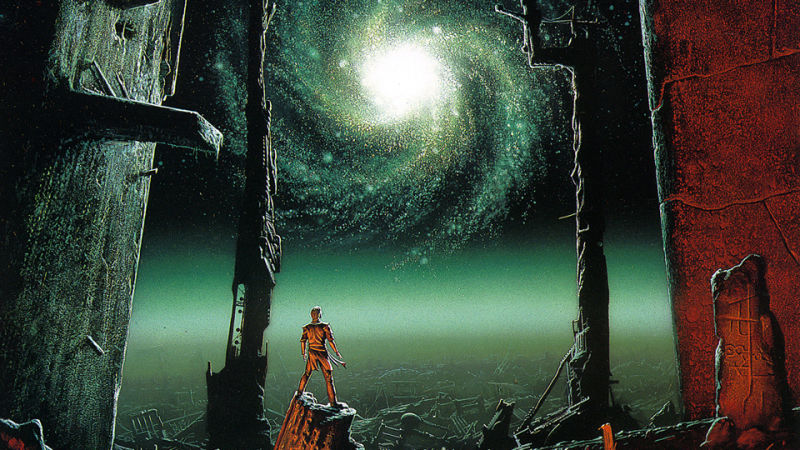

In Isaac Asimov’s Foundation, the character Hari Seldon, a psychologist, sociologist, and statistician, develops a branch of science called psychohistory. His science basically examines the actions and reactions of societal history in order to formulate a predictive model for future macro-societal events.

Seldon doesn’t portend the actions of individuals. The science recognizes that an individual is too limited in sample size, and generally too fickle, to accurately predict its actions. However, a very large group of humans will act, relatively, in a far more predictable manner.

Essentially, the book is about the fall of the fictional Galactic Empire, and by its nature a callback to the fall of the Roman Empire. Seldon’s science indicates that if the Empire were left to its own humanistic devices, it would take 30,000 years for it to completely crumble and reform into a second stable empire.

Instead of waiting for a miserable period of decay, an extended Dark Age, and a subsequent slow regeneration of technology and peace, Hari Seldon devises a “Plan” that, according to his psychohistory, will condense the process to a mere 1,000 years.

The Seldon Plan anticipates when a particular societal crisis will happen. In that pivotal moment, a holographic form of Seldon appears to a major player in humanity to nudge that person in the correct direction.

What is important to keep in mind, is the Seldon Plan does not always make a particular present more peaceful. That “correct direction” can actually be a horrific act when only seen on its own. Condensing a regenerative process from 30,000 years to 1,000 can only be accomplished by blowing up certain traditions and comforts.

A slow decay is imperceptible to most humans. It’s easier to overlook small issues when one is comfortable enough to enjoy the greater good. We are procrastinating gods on all scales. Seldon’s Plan overrides those tendencies.

“Just because something works doesn’t mean it can’t be improved.” Shuri, in Black Panther

Before one begins to lump Seldon in with the “genius savior” trope that painfully continues to dominate our societal conscious, it should be noted that The Seldon Plan was designed to be constantly worked and reworked by the brightest minds of any particular day of Asimov’s fictional universe.

The most intelligent people among us recognize that no plan is beyond reevaluation, regardless of its initial genius. Asimov ended up spinning the concept into an entire series. Some claim the later novels bastardize the original premise. I disagree. Asimov simply allowed it to evolve as science is apt to do.

“The Seldon plan is neither complete nor correct. Instead, it is merely the best that could be done at the time. Over a dozen generations, men have pored over these equations, worked at them, taken them apart to the last decimal place, and put them together again.”

In the above quote, one could simple take out “The Seldon plan”, and replace it with “Science”. Go ahead. I’ll give you second.

For all I know, the world is currently being nudged in the “best direction” by some holographic rendering of science. But in case it isn’t, we need to do a better job of enacting the plan on our own.

Things that probably don’t jive with Seldon’s Plan:

Defending a tradition based purely on the fact it has been around awhile.

If the reason for why you are doing something is simply “That’s how it’s done!”, then you might want to reevaluate. Or perhaps make amends(ments).

I can’t tell you how I know, I just DO!

No, you don’t. No one really does when it comes down to it. The vast majority of our life on earth is spent in our minds, abstractly constructing a “reality” that is in no way free from our biases as an individual.

We don’t truly know what is happening down the street from us. We are right to assume that our favorite cafe probably still exists where we last saw it this morning, but the actual recall and construction of that entity is entirely our mind’s creation.

Even when we are in a room, enjoying something’s tactility, we are still interpreting the object with our individual “software” regardless of the tangibility of our “hardware”.

That is true for everyone. It doesn’t matter whether we are “right” that a tree exists. A mind’s perception of that tree in the first place is still an individual’s perception and hers alone.

And that is only speaking geographically!!! Add in temporal questions, and things get even more inherently unknowable. Afterlife? The 2018 draft? Really? How about after lunch?

Staying in a situation because “it could be worse” / Getting out of a situation because “it could be better”

Okay, this might seem a little confusing, but it is a continuation of the previous fallacy of absolute knowledge.

Some people are paralyzed by the fear of a potentially worse situation so they stay in the known quantity. The fear of the unknown, and thus becoming one who “doesn’t know” drives them to stay in a comfortable situation in order to avoid feeling the fool.

Conversely, a person who falsely thinks he knows a theoretical future to be “true” maybe is undermining a decent current situation out of lust for the theoretical one.

Man, Ben. I guess we can’t win. Are you saying to cut your losses like you implied with Seldon’s Plan , or to suffer, grit your teeth and bear a tough situation?

What I am saying is that we need to eliminate our hubris of knowledge in order to make any rational decision. We don’t know it will work out either way. Don’t grit your teeth and bear it because you know it will “be okay”. It might not be okay. Nor should you break something because you know something better is out there. Maybe there is a high probability of that being true. Be content with probability.

We must accept that the most rational thing humans have ever done is to recognize that we are incapable of acting 100 percent rationally.

We can’t do it. Not as individuals anyway. We are too limited by our unique sensory perception of the world to truly understand another person’s take. We may feel empathy. As a social species, we may happily reflect a multitude of gestures, reciprocating our realm specific needs. But we don’t really understand what it means to be anyone but ourselves. Even if we end up learning to define the amazing connectivity we have as a species, that still doesn’t eliminate the individual perspective.

The idea of absolute knowledge tricks us into believing we can be more correct about abstract things than those from different cultural backgrounds from our own. It creates competition and inferiority complexes about intangible things that have no actual solution.

Ridding ourselves of that way of thinking would be a huge step toward acting with compassion. If we didn’t feel the need to be completely right about a thing at the expense of another person’s “right”, then we’d do a lot better as group.

Value systems, laws, regulations, and the like do need to be put in place. Any rebuild starts with the seemingly unfortunate necessity to destroy the past. That initial explosion is likely to be more painful than a slowly drawn out deterioration. We must have the courage to act. Not because we know it will all turn out okay, but because it probably will.

An abandonment of the myth of definitive knowledge wouldn’t force people to totally disregard their fellow man. Finding direction through probability would only make it easier to evolve our value systems. If we utilize our rationality as much as we can, while acknowledging the limiting factor of our biases, we may be able to maximize our group potential without indulging in misplaced competition. Without a false competition that breeds condescension, we can be more grateful for what we have, even in our biased individual heads.

(Fill in the blank) is neither complete nor correct. Instead, it is merely the best that could be done at the time.

Yep, this is good stuff. I also liked Asimov and his epic perspective. I read the foundation novels as a teenager and also the robot books. The Diamond age by Neal Stephenson is another brilliant sci-fi epic. I basically love anything by Kim Stanley Robinson as well.

In London and just got a chance to read this… I’m a huge Asimov fan and truly appreciate your analogies here Ben! Just awesome stuff!

Awesome

“That’s deep”

Regards,

The Mariana Trench

Hehe, nice.

Nice bit of epistemology here. The Seldon Plan seems utilitarian, no? I’m generally skeptical of that framework when assessing the “goodness” or “rightness” of particular choices (or even policies).

Quite a post by Ben. And what a range of topics from operatic high C notes to Asimov. I took a fun science fiction elective course in college that focused on Robert Heinlein, Arthur C Clarke and Asimov. Really liked that class and very much enjoyed Ben’s non-basketball analytics. Take a curtain call

I have never seen a sports article that says less than this one. http://bleacherreport.com/articles/2760790-where-will-lebron-go-the-truth-is-out-there?utm_source=cnn.com&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=editorial Really? Talk about being guarded. If the LBJ free agency is such an interesting topic, stop being so nebulous and say something Beck. That is the only entertainment value of articles about LBJ free agency. We know the facts. We don’t need a rehashing, and if you are doing a summary then make a conclusion. Talk about click bait. I have never read a longer sports article that ended up saying literally nothing new. Basically to paraphrase, ‘I know where he will go. It will be… Read more »

An excellent think piece. This blog never ceases to surprise me. Foundation is one of my favorite sci fi books and series. I never thought I would read a discussion of its themes here.

Ben: Interesting piece. I haven’t read the story, or much Asimov aside from Nemisis which I found at an old used book store. I’ve been thinking about decay and collapse and rebirth in society and large organizations (like you know, the Earth or the U.S.) for some time. I’m increasingly skeptical of large organizations to consistently make intelligent decisions and to sustain viability. We’re too selfish, dumb, and self-destructive a species to ever get to the large scale of rationality described above. Who sacrifices to make changes across 1,000 years as opposed to 30,000? In fact the larger an organization… Read more »

Take my proclamations of doom with a grain of salt. Fortunately, I’m not always the most rational soothsayer… except when I am.

Genetic engineering is already happening, not necessarily in the form of movies and such but in a much simpler scale.

I just learned about a Chinese cancer treatment with reengineered CAR-T cells. That, along with stem cell engineering/transplants will continue our path towards superhumans :)

Eh. I consider that more genetic therapy as opposed to engineering.

On a lighter note, the robot series is pretty fantastic and I would highly recommend it. It also takes place within the same universe as Foundation and has serious implications for the foundation series. I won’t say anymore for fear of spoilers.

The Seldon Plan doesn’t say that large groups make the best decisions. The large population gives the Psychohistory enough data to accurately predict how those large groups will act. His point is precisely that if left to their own devices, those in power will always prefer slow deterioration because at least they are still in power. When Seldon’s hologram appears, it is more often to take down a huge system that has run its course. Expedite the destruction to more quickly get to the creation. The ones losing power certainly aren’t happy about it. In a manner of speaking, the… Read more »

This is deep. Thanks for sharing. The first thing that came to my mind was the Civil Rights Movement, which seemed to flourish after the “horrific” assassination of MLK.

“If we utilize our rationality as much as we can, while acknowledging the limiting factor of our biases, we may be able to maximize our group potential without indulging in misplaced competition. Without a false competition that breeds condescension, we can be more grateful for what we have, even in our biased individual heads.” The problem with this idea is the simple fact that in the United States (keeping it local) competition and the overall desire to be “better than” is one of the strongest forces that keeps this country moving forward – not necessarily in a positive way. We… Read more »

Ben Werth is the LeBron James of Cavs: the blog.

He’s making me start to believe we’re seeing someone surpass the all-time greatness of Colin McGowan (the Michael Jordan of C:tb).

Wow.

One suggestion though, Ben:

Try to avoid scheduling an hourlong TV special where you surprise all of us by telling Jim Gray which website you’ll be taking your writing talents to next year. No matter how many underprivileged kids are standing behind you.

It was not the best that could have been done at the time.

lol wow

Who does that make you, Tom?

Mike Brown

Bahahahaha

Tom is Dan Gilbert

I’m the Ricky Davis.

hahaha

Cedi-adova- the fan favorite!

Btw- did Mark Neal leave? You doing any radio?

yeah Mark moved. Nope, no radio for me. If mark gets a gig going in Minnesota he told me he’s gonna have me on.

hahaha Much appreciated, and hilarious. Thanks, TK.

Bravo, Ben. I’m not sure where in the Sports Blogosphere anyone can read these types of musings. Sent the article to my wife and a few family members as particularly relevant reading material. Thanks for the hard work in writing it.

Last word today on the Nets. They have 3 patches of light schedule left.

One is right now: at Hornets, Bulls, at Cavs, at Kings. 3 winnable ones. Though 2 are away. Great for us if they whiff.

Second is a 3 game homestand in mid-March vs Mavs, Grizz, & Hornets.

Last is the last three games of the season: home & home with Chicago & at Boston where the Celtics likely rest everyone.

Full Nets update. Wins:

18 = Suns, Hawks, Mavs, Magic, Kings, Grizz

19 = Nets

20 = Bulls

Tonight:

Nets at Hornets

Knicks at Magic

76ers at Bulls

Thunder at Kings

On the tank front:

Nets: RHJ & Lavert still out tonight but team hopeful for Monday. They will be better when those two return.

Magic. Gordon & Vucevic back tonight & Isaacs practicing with G-league squad. Those returns + a pretty soft schedule make the Magic a good bet to surge ahead of the other tankers. Plus, Gordon can bolt so things can’t get too miserable.

Asimov is awesome. Chilhood’s end is an all-time book. Not to mention ‘I, Robot.’

I formerly named my work computer Seldon and the last few iterations have been Deckard. Was it really ~50 years ago I was reading the Foundation series and LOR as well. Asimov was far more appealing than Tolkien while Heinlein was for an even younger me. I have a long flight coming up and what could be better than to hear about The Mule on an audio version. Maybe Patrick Stewart will be the reader. And I will resurrect Seldon as a device name for my next Core I7 8th gen laptop. And back to BB, LBJ is right to… Read more »

“Defending a tradition based purely on the fact it has been around awhile.”

There’s wisdom in airing on the side of caution (maybe we can express this as “preserving traditions”) that maintain stability. Order tends to decay.

Erring not airing. Kids these days.

ouch.

“liberals” and “conservatives” (If you believe the dichotomy has any basis in our shared perception of reality).

we use heuristics because they are good enough

Sometimes “order” is a great evil depending on how it is kept and how many benefit from such “order.”

Of course, to be fair, change when it happens through violence can be a greater evil sometimes.

man that situation with the spurs / leonard seems to be getting more tensed—–I would offer that Brooklyn pick / t.t. / and whatever other player ( ante / j.r etc ) for leonard

WOW —I feel educated / enlightened every time I read one of your posts Ben —great job —EMOTIONS will never allow us to make rational decisions 100 %of the time ——NEED YOUR “MASTERPIECES ” MORE OFTEN !!!————finally thurs has arrived —-am anxious to see (hope ) the cavs can pick up where they left off—–sounds like practice(s) have been very upbeat / energized / positive —–the only ” BARKING ” IS THAT OF COMMUNICATING ON DEFENSE —-NOT AT ONE ANOTHER !!

Great work, Ben. Your ability to make complex subject matter more accessible through context is a joy to read.

Preach it. Great read.