#CavsRank Villains: No. 1, “Miami” LeBron

2015-09-10

Editor’s Note: A few weeks ago, we had seven CtB writers rank the biggest villains in Cavs history. We tallied up the results and they were a surprise to me as much as anyone. I thought Jordan would win in a landslide. Using a reverse ranking system which gave 25 points for No. 1, and one point for No. 25, LeBron received 168 points, just edging out MJ who nabbed 166. Interestingly, LeBron garnered only two first place votes while Jordan grabbed four. (Ted Stepien received one). But one writer game-theoried the ballot and ranked MJ fifth, which pushed LeBron to the top (the same writer had the Heat listed as No. 2). After thinking about the results, I’m glad it turned out the way it did.

David Wood

I didn’t hate LeBron James for going to Miami or – after about a year – even the Decision. My ethos of, “I’m still a LeBron fan till I die, but there’s some room for hate in that fandom,” started after game five of the 2010 series against the Celtics when I looked at who LeBron was at that time. That game he went 3-14 for just 15 points to go with six rebounds and seven assists. All of Boston’s starters, aside from Kendrick Perkins, scored more than him. The Cavs lost 88-120. It was a straight up stomping. The Celtics did whatever they wanted, as the Cavs messed with their rotation, lacked motivation, and got booed by their own fans with over 22 minutes of game left. Bill Simmons summed the game up pretty well in a diary entitled, “The end of pro basketball in Cleveland?” if you want to relive it.

–

My LeBron hate seed was planted all the way back when the King entered the league in 2003, even if I didn’t know it at the time.

I’m not entirely sure who first said the phrase, “LeBron James won the genetic lottery,” but it’s an obvious enough statement that it could have been said by anyone. At just 18 years old, LeBron was 6’7” and 240 pounds. His out of high school body was as good as or maybe even better than the best bodies in the NBA. And, let’s not forget, he was as coordinated, strong, and smart as the best guys in the league. He was the robot you would design if you wanted to take over the NBA single handedly: able to pass like a point guard, able to score like a shooting guard, able to cut like a small forward, and able to hold his ground like a center. In just threes years in the league, he upped his weight to 250 pounds (270 pounds at times in later seasons). All of the extra weight being just muscle. LeBron has arguably the most natural talent of any athlete, ever.

Talent is the word I want to really focus on.

Not only is Will Smith a great actor, he is a great philosopher. Looking back at LeBron’s time in Cleveland, you see that the King really relied on his raw talent. It’s not necessarily a bad thing seeing as he consistently scored above 25 points and had at least five rebounds and five assists a night after his rookie year.

After his rookie season, LeBron improved as a shooter ever so slightly, but still wasn’t amazing. As a rookie, he had a true shooting percentage of 48.8%. During the 2004-2005 season the King became a little more comfortable and his true shooting percentage reached 55.4%. His true shooting numbers hovered around that area until the 2008-2009 season when he was able to increase his true shooting number to 59.1% thanks to a Cavalier team with near perfect chemistry and construction. Check out John Krolik’s description of that season for LeBron (This article is also wonderful if you want a more detailed history of LeBron’s development as a player):

With Williams and West spacing the floor and keeping the ball moving on the perimeter, Anderson Varejao and Ben Wallace making smart cuts to keep the defense honest on the weak side (Ben Wallace used cutting and passing to be FAR more effective than he should have been offensively that season), and gigantic former point guard Zydrunas Ilgauskas keeping the ball moving from the high-post and hitting release-valve 18-footers, LeBron finally had the toys he needed to play with. There were some new sets to free Mo Williams for corner threes on picks, or get LeBron free on the weak-side, but mostly it was LeBron making the defense react on every possession and having four teammates on the floor with him at all times who knew how to make a reacting defense pay.

LeBron could no longer be the total focus of defenses, unless they wanted to be burned by other guys. The King also started making more long twos and more threes that season, which helped him become a more effective “shooter”.

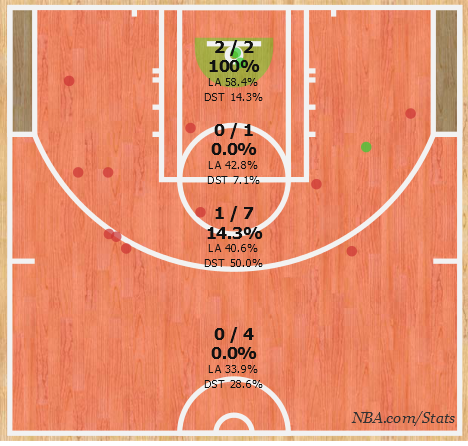

However, he was still hitting less than 35% of his deep threes during these pre-Miami years and had the bad habit of taking long 2s (defined as 16 feet out to the 3-line). In fact, during his first seven seasons with the Cavs 24.5% of his shots were long twos, the most inefficient shot in the game, and he made 37.5% of them. That number isn’t entirely dreadful, but when you make shots at a 70% rate around the rim it is by comparison. LeBron’s final season with the Cavs, 26.2% (the second highest percent of his career thus far) of his shots were from that dreaded long 2 zone.

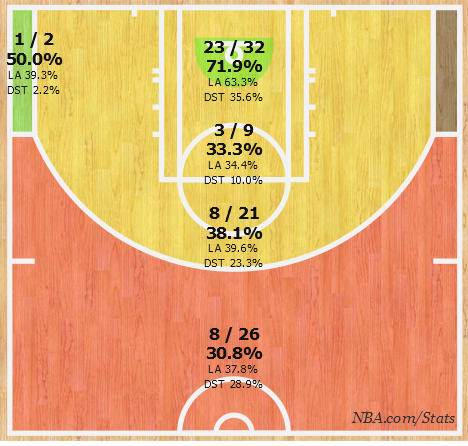

While in Miami, 22.5% (just 19.3 during the playoffs) of the King’s shots were long 2s and he drained 41.4% of them. He also shot 36% from 3-point land in Miami. It’s pretty apparent he developed better shot selection, and really improved his overall playing while on his four-year vacation. Bron learned how to post-up and learned discretion in shooting, his true shooting percentage stayed above 60% his entire time at the beach. He also shot 79.6% percent at the rim his final season there, which is absolutely absurd.

–

Let’s flashback to arguably LeBron’s best performance as a Cavalier. His best display of pure talent. LeBron was just 22 years old. In 2007, with the Eastern Conference Finals tied at 2-2, LeBron went head to head to with Detroit Pistons, who had knocked him out of the playoffs just one season before, in a pivotal game five. The game ended up going to overtime. The King scored 29 of the final 30 points in a double overtime win. Bill Simmons gushed:

This wasn’t just about the improbable 29-of-30 points barrage down the stretch, those two monster dunks at the end of regulation, the way he perservered despite a crummy coach and a mediocre supporting cast, how he just kept coming and coming, even how he made that game-winning layup look so damned easy. Physically, LeBron overpowered the Pistons. This was like watching a light-heavyweight battling a middleweight for eight rounds and suddenly realizing, “Wait, I have 15 pounds on this guy,” then whipping the poor guy into a corner and destroying him with body punches. The enduring moment was LeBron flying down the middle for a Dr. J retro dunk and Tayshaun Prince ducking for cover like someone reacting to a fly-by from a fighter jet. The Pistons wanted no part of him. They were completely dominated. They didn’t knock him down, they didn’t jump in front of him for a charge … hell, they were so shell-shocked by what was happening, they didn’t even realize they should be throwing two guys at him.

Simmons summed up what LeBron’s first stint in Cleveland would come to be known for in my mind:

Put it this way: They won’t need to change the rules to protect LeBron. If Jordan was a receiver, then LeBron is one of those scary tight ends who runs a 4.35 40, outsprints safeties and occasionally carries five tacklers into the end zone just to see if it can be done. Physically, he’s the most imposing perimeter player in the history of the league. Nobody else comes close.

Just look at these highlights.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JHaSiWClteQ

Watching that video should make one thing really clear. LeBron’s go to move at the time was absorbing contact, taking his two steps unphased, and making a pass or finishing. It’s unworldly how strong he looked. At that time, a semi-truck could have driven onto the court, blasted LeBron in the shoulder, and the King probably would have completed whatever it was he wanted to do: pass, shoot, or dunk. The King’s go to move was putting his head down and getting to the rim. It’s the same move that he still shows when he doesn’t want to work someone over in the post. It’s genetics.

–

Unfortunately, for the King, the Celtics figured out how to defeat those genetics. In game 5 of their 2010 battle, the Celtics opted to let Paul Pierce just focus on LeBron. He was going to keep the King from getting to the rim. A lot of times this meant sagging off of him and conceding the 3-pointer or mid-range jumper. It worked. The King’s talent couldn’t overcome the Celtics. For the series LeBron made just 7-24 shots from behind the arc.

LeBron bounced back the next game putting up a triple-double, but the Cavs still lost the series in six. The King was still one of the best players, but after that game five, we all knew something was up. LeBron had no go-to move based on refined skill. If a team could cut LeBron’s physical presence down, his skill set couldn’t make up for it.

Another part of the issue was that LeBron still thought his shot was one of his skills in 2010. That season he took five 3s a night hitting just 33.3% of the time. Only 28 others guys in the NBA took at least that many triples a night. Of those 28 guys, only Stephen Jackson made less of his long balls hitting only 32.8%.

Now, back to game five. My hatred for the King started after that game because it was then that I saw he had probably been coasting just a little bit on his natural gifts. Up until that point, I had never noticed this. I always blamed the Cavs’ playoff failures on lackluster supporting casts, bad luck, and outside factors. I can’t blame him though. I was always willing to say “Good job,” when it came to LeBron, which was actually the problem. He could do no wrong and I usually defended him, as did most of Cleveland, when people criticized his game.

Fast forward to the 1:40 mark of the video.

Terence Fletcher: I told you that story about how Charlie Parker became Charlie Parker, right?

Andrew Neiman: Yup, Jo Jones threw a cymbal at his head.

Fletcher: Exactly. Parker’s a young kid, pretty good on the sax. Gets up to play at a cutting session… and he fucks it up. And Jones nearly decapitates him for it. And he’s laughed off-stage. Cries himself to sleep that night but the next morning, what does he do? He practices. And he practices and he practices with one goal in mind: Never to be laughed at again. And a year later, he goes back to the Reno… And he steps up on that stage and he plays the best motherfucking solo the world has ever heard. (beat) So imagine if Jones had just said: “Well, that’s okay Charlie. Eh… that was alright. Good job.” Then Charlie thinks to himself, “Well, shit. I did do a pretty good job.” End of story, no “Bird.” That, to me, is… an absolute tragedy. But that’s just what the world wants now! People wonder why jazz is dying. (beat) I’ll tell you man. And every Starbucks “jazz” album just proves my point, really. There are no two words in the English language more harmful… Than “good job.”

That scene is very applicable to LeBron. The world came down on him the season after he left. He felt it; he failed that first year in Miami. During the Finals against Dallas, he would again take too many 3s, even though he wasn’t hitting them. LeBron’s play allowed the world to throw a cymbal at his head. The NBA laughed and no one said “good job,”when the King lost this time. There was no scapegoat. His team was stacked. The world said he was choking and his talent couldn’t save him. But, that was what the King needed. He won the title the next year.

Ironically, it was probably all of the Cleveland and general hate that helped him work on the skills he needed to be good enough to win a title. So Cleveland fans rejoice, you all sort of have a claim to James’ Miami titles. And, you all have a a claim to his now legendary skill set. Those skills are what makes it all okay that he’s back. I also pretend the four years in Miami were just a quasi-Hakeem camp. I just hope the King still has enough of his game five Detroit destruction talent left to make his four year trip worth it.

All stats from Basketeballreference.com unless noted otherwise.

Nate Smith

LeBron James is the greatest player in Cavs history. He tops almost every career statistical category, and probably will top them all by the time he’s done. LeBron is rivaled only by the immortal Jim Brown as the greatest sports figure in Cleveland history. Yet a year-and-a-half ago, when a group of Cavs blogs got together to turn out #CavsRank and rank the best players in Cavalier history, the King was ranked only No. 2. He was topped by Mark Price, a great player and by all accounts a great person. But Mark Price isn’t the force of nature that LeBron is, and there’s no chance that he’ll go down as the greatest basketball player of all time, like LeBron has a good chance of doing. At that time, though, LeBron was “Miami LeBron.” If we bloggers retook that same poll 17 months later? There really couldn’t be any other No. 1 other than LeBron James. He’s the team’s greatest hero, greatest player, and most notorious villain.

People try to forget the levels of insane hate and agony LeBron’s departure caused. LeBron’s tale is one of a kind. No player as great as LeBron has ever had a story like LeBron James. We watched him in high school when he became a national phenomenon at 16. We celebrated joyously when the Cavs won the lottery to draft him. James traveled just 30 miles north to Cleveland to play. He became arguably the best player in the league by his third season. And we all watched him grow up before our very eyes. We were all invested in that story, and his departure devastated our egos and broke our hearts.

LeBron’s departure for South Beach wasn’t “The Shot.” It wasn’t Ted Stepien making the team a national joke, and running it into the ground. Michael Jordan’s greatness was, while agonizing, explicable. We could see it with our eyes. And Ted Stepien’s incompetence was apparent from very early. If the man had moved the Cavs to Toronto, we’d all be living different histories. Stepien would be our Clay Bennett. But Larry O’Brien and the Gunds saved the Cavs. No, what LeBron did was worse.

I’ll spare you a recap of the details. We know the events of July 1, 2010 like we know the back of our hands. We’ve all wrote about it here ad nauseum. There’s four years of LeBron agony and anger in the archives of this blog. Tom wrote a three part series on The Decision entitled, “Why I want LeBron to Fail (Forever).” He summed up why LeBron’s exodus hurt so damned bad.

The media and the trolls could take their uninformed pot shots at Cleveland but they certainly couldn’t de-legitimize the game’s best player, and our homegrown son, not on our watch. And that is how he became more than a player playing a game – he became our face to the outside world. That is why we hung a monstrous Christ-like image of a man in our city – that is why we bought Witness T-shirts, that is why we took it so personally when he refused to represent the Indians – since they were also a part of our collective psyche. It became unhealthy...

LeBron’s decision, intentionally or not, meant this to me: “I don’t care at all about you or your city.” Quite simply, there are a lot of people that don’t care about me or my city – in fact MOST people don’t. But this stung – it really really hurt. It cut both ways. I didn’t spend thousands of hard-earned dollars on t-shirts, shoes, jerseys, posters, and other memorabilia bearing the name of most people – I bought LeBron’s… I did it in support of LeBron. I fought an NBA sub-culture war, (quite possibly the silliest thing I’ve ever admitted to) in defense of LeBron’s honor. Because to me, LeBron became Cleveland – and I will always support Cleveland.

I felt rejected, betrayed, and those feelings quickly gave way to embarrassment and shame. Embarrassed that I would go so far and expend so much energy on someone that did not even know I existed. Someone that, at his core, could literally not care less about what I thought of him. Someone who’s “fans” existed solely to elevate his already incredible ego – disposable fans. It was the ultimate disrespect.

[From Part II]

LeBron quit before he started. He quit because he never went all-in. He quit on his teammates, he quit on the Cavalier franchise, he quit on Cavs fans, he quit on NorthEast Ohio, and he quit on the game of basketball.

LeBron didn’t quit on his teammates in the box score – he quit when he made himself bigger than them. When he preached to us about his love for his teammates for years and then left them with the same constant anxiety as us fans. They had no idea what his plans were, where he was going. He didn’t fill them in at all. He didn’t even hint at it.

Yes, LeBron hurt us badly, from Dan Gilbert, to the fans, to Mo Williams. LeBron left us all searching for answers and wondering why we weren’t good enough. The truth is we had heaped a ridiculous amount responsibility on one young man’s shoulders. Few people can carry that weight: governors, presidents, mayors, civil rights leaders, CEOs. Asking a 25-year-old basketball player to be Atlas was, in retrospect, ridiculous.

But what made Jame’s departure so villainous, was not that it broke our hearts our damaged our regional pride. It was the fact that our reactions to it turned us into worse people. Dan Gilbert wrote a letter in Comic Sans that I’m sure he’ll regret forever. He went on talk radio shows and made ridiculous accusations and proclamations about LeBron’s future failures. Mo Williams was never the same. I spent four years referring to LeBron as LeFraud, LeQuit, and a thousand other all too cute LeNicknames. I’m sure Tom will cringe when reading some of his wishes for LeBron’s perpetual failure. “Miami LeBron” became the antitheses of Cleveland LeBron. While Cleveland LeBron was held up as a “Christlike figure,” Miami LeBron became the magnet for all our blame, derision, and irrational anger. It was equally ridiculous.

And let’s not forget that LeBron got a little nutty himself. We all know the “Welcome Party” video. Where LeBron predicted eight Heat championships. And there was the 2010-2011 season where LeBron seemed to relish his heel turn, and the villain role. But by and large we acted just as insufferably. The flaming jerseys were not the face of Northeast Ohio that we wanted to show the world. In the wake of Forclosureville a wretched recession, and The Decision, we kind of lost our minds. I mean we rationalized re-hiring Mike Brown for Christ’s sake. I didn’t start getting mine back till I started writing here.

It took me a long time to realize that what made this area awesome had nothing to do with LeBron. It had something to do with this feeling that we’re all in it together…

And even if you find the idea of regional allegiance bizarre, as Colin did in one of his best pieces, I still hope there’s a character to the region that rubs off on even the most distant fan. “Cities –” Colin wrote, “though they’re really just a mass of flesh, concrete, and steel—breathe. They are frighteningly organism-like. And what better way to celebrate that almost-organism than by watching your favorite sports team— ambassadors of your favorite city.” I still hope that the guys on my team represent some of what I value: hard work, individuality, class, humor, diversity, decency, effort, originality… And I hope they can split double teams, hit corner threes, and convert around the basket.

There is a point at which players – those ambassadors – have been a part of the team and the area for so long that they’re not “players” any more. They’re people. They exist outside of the game. They become part of the mythology of the realm. Instead of our team/our place leaving their marks on them, they leave their marks on us. Jim Brown, Bernie Kosar, Bob Feller, Jose Mesa, Jim Thome, Omar Vizquel, Zydrunas Ilguaskus, and LeBron James (for good and ill), have imbued our folklore with spirits that it didn’t have before they were here.

So we all spent four years healing, and growing up a little bit. I, for one, learned to take sports less seriously. I think part of me at the end of LeBron’s Heat run even empathized with LeBron’s inability to conquer the Spurs: a perfect basketball machine.

In the last five years, we’ve become better people, I hope. LeBron Jame’s legacy on his Cleveland return continues to grow, and transcends the arbitrary notion of a championship. He’s committed himself to helping kids get to college, and helping adults get their GED’s. As LBJ said in his “I’m Coming Home” essay, he’s committed to something that means more than a championship: helping make this area a better place to live, work, and raise a family.

I feel my calling here goes above basketball. I have a responsibility to lead, in more ways than one, and I take that very seriously. My presence can make a difference in Miami, but I think it can mean more where I’m from. I want kids in Northeast Ohio, like the hundreds of Akron third-graders I sponsor through my foundation, to realize that there’s no better place to grow up. Maybe some of them will come home after college and start a family or open a business. That would make me smile. Our community, which has struggled so much, needs all the talent it can get.

LeBron is shouldering some of the weight that we always wanted him to before he left. He didn’t have to do this. He could have stayed in Miami. He could have gone to New York, L.A., or any city in the world. He could have stayed our greatest villain. But he chose to return, forgive, and carry that weight, despite everything that he said and we said. In choosing that, instead of having it chosen for him, he’s become our biggest hero.

I finally got through all the crazy! Goodness this was funny. Cannot wait for the championship season to begin. Mo freaking Williams is back. So great!

When was the last time there was this much heated debate on CtB? It does bring up some good points: 1. Once a villain, always a villain? This is a reasonable point to disagree on. The Raoul view is that at about 11:30 am one day early last summer, when the news hit the airwaves about LeBron returning, LeBron was removed from the villain list. The opposite view is reasonable. 2. Should we really look deeper into Gilbert, Brown, etc.? The Raoul theory is that excessive reexamination of history just makes you crazy. There is plenty of bad stuff to… Read more »

It’s funny. LeBron was a completely uncontroversial idea when we took the poll and when we filled out our ballots. I was surprised when I added up the scores, but I said “huh” and moved on. As I noted at the beginning of the piece, some of why LeBron was named No. 1 was because of the scoring system. I didn’t give any extra points for a “first place” vote. If I had, No. 1 would have gone to Jordan (he got four first place votes while LeBron got two). The thought that this could generate discussion and debate was… Read more »

Cols, At least admit you understand where people are coming from with this. No one really minds your opinions or the schtick if I can call it that. In fact, you live-commenting as you freaked out while listening to one of our podcasts might be my favorite CtB moment ever. I BEGGED Nate not to ban you and his hand was stayed. We’ve all grown to realize that you are a valuable member of this small community. So don’t accuse of clickbait – you know that is not true. In fact, this blog is the ANTITHESIS of Clickbait. Our site… Read more »

OK, sorry about that.Not click-baity. How about slate-pitchy? That might be a better way to go about it. Nate will understand.

Sorry, sometimes I get too emotional, I’ll try to tone it down a bit.

Alright thanks for the apology and appreciation. Thank YOU for being here. Carry on

Slate-pitchy=Click-baity. It’s not click bait. It’s just an article about a poll we took.

#Slatepitch would be “Why LeBron leaving was the best thing that ever happened to the Cavs.”

And yes, I totally appreciate all the work you guys do. Even if I vehemently disagree with this hot take.

That you didn’t read.

Wait a minute, I thought all you guys got rich from this blog?

Once again, I need to point out the absurdity of this ranking.

The Cavs from when the Mark Price era ended until LeBron arrived was a complete basketball wasteland.

The Cavs from when LeBron left until LeBron came back was a complete basketball wasteland.

So put him as villain number one? He saved Cleveland basketball, and that is not hyperbole. It is the truth.

Sigh… is it pot-brownie-o’clock yet?

You think we can take a print out of Cols comments to a Dr. here in Cali and get a scrip?

I think Cols bakes his own, but might have a rule about not baking before noon…

Pretty sure Cols is Chairman of the Colorado Wake And Bake committee.

You actually don’t need to point it out again. The first 27 times was enough.

Well done Cols, You just answered your own question.

Here is a short, bullet-point summary

-Basketball sucks in Cleveland

-LeBron Comes

-Basketball is great in Cleveland

-People have hope

-Finals Appearance

-BOOOOM LEBRON IS GONE

-Basketball is MISERABLE in Cleveland

-People HAVE NO HOPE

Get it?

Here’s the thing, and I’m sure the LBJ lovers will dispute this and give all kinds of excuses, but I believe this to be true: If LBJ was the player in 2009 that he became in 2012-13, he would have fulfilled his promise and won us a title. You can point to failed free agents signings, draft picks, Mike Brown, etc etc, but the reason we didn’t win the title was because Lebron wasn’t good enough yet. He refused to develop a post game. He refused to stop hero chucking in important games. He didn’t have the mental chops yet… Read more »

Yeah, LeBron’s fault that 2009 team didn’t win the title. 29.7 ppg, 8.6 assist per game, 7.3 rebounds per game.

Yep. All on LeBron. Never on the GM WHO GAVE THEM A TEAM THAT WON 20 GAMES THE YEAR AFTER HE LEFT!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Your response exactly proves my point. That you don’t know why is a failure on your reading comprehension school teachers.

Joey B, Lebron had many failures. But 2009 was not one of them. He may not had a post game then but he was at the absolute peak of his athleticism. Lebron supplied the Cavs with a 38-8-8 averages in a losing cause to the Magic in the ECF. It ranks among the very tops ever in terms of play-offs series PER. On a per game basis, the entire 2009 play-offs probably ranks as Lebron’s personal best (just thoroughly dominated the Pistons and the Hawks in play-off sweeps), at least numbers wise . Offense was not a problem as Lebron… Read more »

This is revisionist history. I could just as easily say the Magic won that serious not because of our poor defense, but because of their above-average shooting splits. Dwight Howard has never shot 75% from the line since. The whole team’s shooting regressed next series in the Finals. As good as LeBron was in that series (which I agree was his best ever) he would’ve been even better if he’d had a post game back then. If something’s not perfect, there is room to improve. Was it Mike Brown who regressed in 2010? Or was the players? The team chemistry… Read more »

I could also argue that more than above-average shooting of the Magic, Mike Brown was exposed (again) as an overrated defensive coach. Sure Lebron quit in 2010 but how do you justify keeping fat Shaq and decrepit Antawn Jamison who were getting torched by the likes of Big Bay Davies? You still have to explain to me why Brown insisted on putting Ben Wallace on Rashard Lewis and Delonte West of Hedo. And I’d like also to ask you a question I asked EG: If Brown is not a horrible coach, how come he lasted only one year in LA… Read more »

If we’re being honest, I don’t remember enough of that series to dissect how much Delonte defended Hedo and Wallace on Rashard, when they did so, and who the other guys were guarding at the time. I’ll concede that those are mismatches, but I don’t think Ben Wallace was playing huge minutes that series and Delonte was probably switching onto Hedo when he guarded him. I really don’t think any coaching job could have saved that Cavs team from the buzzsaw that was the 2009 Magic. Brown’s defensive philosophy doesn’t translate to the modern NBA because it doesn’t place enough… Read more »

Not to mention the steroid use…

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/07/sports/basketball/07nba.html?_r=0

My point is that, for 5 years, there were many of us who saw that while Lebron was at the peak of his athleticism, he didn’t have the leadership skills he needed to win a title. Yes, Mike Brown was outmatched. Yes, Ferry made bad moves. But that 2009 team was good enough to win the title. And LBJ, like Brown and Ferry, failed to win it all because of mistakes the ALL made. LBJ could’ve been better, even as good as he was. It might not have shown up the box score. He never averaged more points per season… Read more »

Honestly Joey, this so-called leadership is way way overblown. Bulls former GM Jerry Krause got it right -organization wins titles, not just players. You win titles by getting a good coach and front office to put a great talent in a position to succeed. The Cavs never did that. Was it really Michael Jordan’s leadership that propelled the Bulls to 6 titles or was it the combination of MJ’s transcendent talent to go with the hiring of the great Phil Jackson and drafting and development of Scottie Pippen and Horace Grant (later replaced by Dennis Rodman) and the FO foresight… Read more »

Mike should probably not have trusted a guy named Vincent Puma…

http://espn.go.com/nba/story/_/id/13625522/cleveland-cavaliers-mike-miller-sues-recover-money-lost-ponzi-scheme

Good points, Evil Genuis. But 1) Why would Gilbert move the Cavs when its main attraction is a hometown hero? It would have been an epic PR disaster and probably a bad fiscal move. 2) Sure, Gilbert wasn’t a tightwad, but let’s not confuse activity with productivity, and willingness with ability. 3) This was exactly the gist of my contentions, Lebron would have never left (and therefore no The Decision and subsequent jersey burnings , etch) if Gilbert gave him a half-decent coach and a proven GM. Just to reiterate one of my salient points, who’s dumber than a guy… Read more »

1) I said moving the team would be the equivalent of the hometown hero leaving 2) The Cavs went 272-138 after Gilbert took over the team and averaged 55 wins per year with a Finals appearance (not exactly unproductive) 3) Gilbert made mistakes, but never stopped trying to get it right. His biggest mistake might have been kowtowing to LeBron as much as he did when he was here the first time (what choice did Ferry and Gilbert have but to sign the ill-fated Larry Hughes deal after Ray Ray and Michael Redd both re-signed with their teams for max… Read more »

1) Point remain, where would Gilbert move the team that that would make fiscal sense and wouldn’t be a PR disaster? 2) Sure Cleveland went 272-138, an average of 55 wins when Gilbert took over. But was that a product of Gilbert’s sound decision making or rather of Lebron’s greatness? For crying out loud, the Cavs were a lottery team and the league’s worst over-all franchise in 4 years Lebron was in Miami. LeBron came back and suddenly the Cavs went from a 4-year hell to two games away from a title despite missing three starters while playing with a… Read more »

1) Clearly you are missing my point that I am using to equate the concept of Gilbert moving the team to LBJ leaving the team as being the “villain” level equivalent (and anyway, wasn’t LeBron’s move an epic PR disaster? he was booed everywhere he went outside of Miami). 2) Not discounting LeBron’s greatness one bit, but my point was that Gilbert spared no expense. He didn’t and he hasn’t yet. I never said it was his sound decision-making, merely his desire to win and to not let the financials get in the way of that (which many owners do).… Read more »

Don’t worry OG-EG. I don’t think people are understanding what “Villain” means. Everyone is using words like “mistakes” and “no productivity.” These do not translate to villain. LeBron was a villain for leaving, and a hero for returning (FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF A CAVS FAN).

Great Job EG and the rest. Don’t think this was an “attempt to be edgy/clever.” It has a ton of merit and makes perfect sense.

Using someone leaving their father as an analogy for why LeBron left is a poor attempt at being “edgy/clever.”

Explain to me how the analogy is a poor attempt? You and EG simply could not satisfactorily defend the willingness to spend money as a way of compensating for egregious and hideous mistakes so you simply dismiss my analogy.

EG, you say I am missing your point in the concept of Gilbert moving his team, Enlighten me then- how is it even a concept, let alone a discussion? What is there to gain in entertaining such concept? How does Gilbert profit from this concept if taken to realization? It’s a no brainer and no brainers shouldn’t get any credit and deserve no explanation or rationalization. Should we credit the Republicans for not trying to secede from the United States after losing the presidential elections in two consecutive years? Should a Calculus teacher applaud his students for knowing basic arithmetics?… Read more »

Very simply, my point about the concept of Gilbert moving the team is that would be a fundamental reason to call an owner of a sports team a villian. If Ted Stepien had succeeded in doing it, rather than just threatening to do so, then he would have been number one on this list. That’s all. Just giving you a fundamental reason why Dan Gilbert would be looked at as a villain if he chose to move the team. It’s a hypothetical that I was using to give you an equivalent to LeBron’s betrayal, as seen by many Cavs fans,… Read more »

The problem with the domestic analogy here is that it implies the kid had no choice in becoming a murderer and drug addict. Everyone has a sob story, everyone has people to blame, but at the end of the day we are the owners of our decisions. If that kid became a murderer I don’t care what his upbringing was like — he is a terrible person. That is why LeBron is the #1 villain: he made his own Decision to leave us in humiliating fashion. Doesn’t matter who influenced that decision. Besides, you can’t call the LeBron 1.0 Cavs… Read more »

We discuss this somewhat on Friday’s podcast. And some of this was on LeBron who was… difficult to work with at times. Gilbert may deserve more than a little blame for enabling him. I agree there were better options than Mike Brown, both times. I hope Griffin and Blatt have the team in better hands now. I believe they do.

I know I am beginning to sound like a Lebron fanatic, but I simply want to put things in perspective. So Lebron was difficult to work with at times. So what superstar isn’t? AGAIN, if Lebron was such a bad guy, how come Mike Brown lasted 5 seasons with him when he could only last a season with Kyrie and a shortened season (and 5 games) with Kobe? Eric Spoelstra is still in Miami and if I remember right, it was Wade who openly has gotten into it with him, not Lebron. Wade has also openly gotten into it with… Read more »

Enabling what? Enabling LeBron to carry your team to the title game and then to some of the best records the Cavs have ever seen? Gilbert’s one fault was he stuck with bad GM Danny Ferry and horrible coach Mike Brown for too long.

Putting the blame on LeBron for Ferry’s stupid personnel decisions is nuts. It’s insane. And it needs to stop.

Enabling LeBron to be a petulant prima dona who wouldn’t commit? You have a lot of blame for Ferry, and not a lot of alternative solutions.

Petulant prima donna? Only the guy who put the Cavs on his back from 2005-2010. Only the guy that kept the Cavs from losing 50-60 games year in and year out.

If Ferry didn’t suck at his job, he would’ve stayed. Blaming LeBron for personnel decisions made by the GM? It’s crazy and nuts. Stop it.

Once again you fail to answer the question. Name some alternative actions for Ferry that would have improved the team.

Hey Cols… here’s a link to the top 10 free agents from 2005… tell us how you’d have GM’d it differently…

http://www.nba.com/features/freeagentpreview_050705.html

That’s easy. I’d sign Ray Allen. Boom Title, History changes.

When would that have happened? Allen signed a five year extension with Seattle in 2005. On July 1st, 2010, he re-signed with Boston (as LeBron was making his mind up whether to return to Cleveland or not). So you’re saying that you’d have signed Allen at the beginning of 2010, and then James would have re-signed in Cleveland too? Your narrative is just fantasy.

And the next guy up, Michael Redd, also resigned with his home team… and then got injured and was never the same…

Not to side with Cols, but I think Dan Gilbert deserves at least a 1b in the hierarchy for simply mismanaging the Cavs franchise. Gilbert bought the Cavs in the midst of Lebron’s second year, a time when they were still in the thick of gaining a playoff spot. Gilbert was said to be meddling too much in Paul Silas’ coaching and Jim Paxon’s FO job that it sent the Cavs in a disarray and the lottery again. AT the end of Lebron’s second season, it was very, very clear that he can potentially be the greatest open court player… Read more »

Three Gilbert rebuttals: 1) Dan Gilbert never threatened to move the Cavs (the owner equivalent of LeBron leaving) 2) Dan Gilbert has never once hesitated to open his checkbook to try and make the Cavs the best possible team (we’ll see what happens with TT, but offering $80M is more than fair) 3) Dan Gilbert (right or wrong) was the ultimate voice for heartbroken and frustrated Cavs fans when he wrote his letter (unfortunately in comic sans) Has Gilbert made mistakes? Absolutely. Every owner does. But the mistakes he made were in trying to give Cavs fans the best possible… Read more »

I dunno. I disagree with the general Mike Brown hate. He got LeBron to care about defense. He coached 66- and 61-win teams with Mo Williams as the second best player. He won Coach of the Year in 2009. He was the mastermind behind an elite defensive squad for 5 years. When you think of the great defenses in the past 15 years, the Pistons, Celtics, Spurs, Lakers, Pacers, and Grizzlies come to mind. The Mike Brown Cavs are right up there with them. Those are not the accomplishments of a bad coach. His defensive principals were outdated by 2010-11… Read more »

I didn’t hate Mike Brown, but I could see why some people would have him on their list of villains. I agree with you about his impact on LeBron defensively (see my comment below).

Yup I just saw that comment after posting. Good stuff! Like, totally same wavelength, breah!

I have often maintained that Mike Brown’s defensive concept is like a powerful truck with no higher gear or 4 x 4 capabilities. It’s powerful on terrains but has nowhere to go when stuck in a mud. That is why the Cavs performed better in the regular seasons but regularly bombed out in the play-offs when teams adjust and throw major and subtle tweaks. Stan Van Gundy made him his bitch in 2009 and not because the Cavs couldn’t score enough. A fat and an ancient Shaq and a defensively challenged Antawn Jamison were clearly being torched by the Boston’s… Read more »

You’ve got a really skewed memory of what happened in 2009. Unless Van Gundy was the one handing out the roids to the yolo crew (Lewis, Turkoglu, Pietrus and Alston) or electroshocking Dwight so he’d somehow shoot 75% from the free throw line, then he hardly made Brown his bitch in that series.

And Brown had nothing to do with LeBron’s 3-15, 15 point Game 5 against the Celtics.

You should probably go back and watch some Hardwood Classics…

The roids accusation is speculation even in its best merit. How do you justify putting post defender Ben Wallace on a long range bomber Rashard Lewis? Why put Delonte on Hedo? Dwight got hot from the line because he got his groove and rhythm due in large part to Brown’s outdated defensive concepts.

And you blame Lebron’s one bad game for the Cavs ouster? That’s nitpicking! How many times did Lebron save Brown from bad coaching?

Ts.Tsk,Tsk.. EG, sarcasm is the lowest form of wit. You’re better than that. I may argue passionately with you but I was never disrespectful.

Apologies for seeming disrespectful with the last line. It was meant as playful sarcasm. Sometimes I can come off more abrasively than I plan to.

Here’s some roids evidence for you… http://sports.espn.go.com/nba/news/story?id=4381822

And even though it was caught later, here’s some more… http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/nba/2013/02/13/orlando-magic-hedo-turkoglu-nba-suspended/1917161/

Dwight, for the record, averaged 55% from the FT line for his playoff career. He somehow shot 75% against the Cavs. That kind of anomaly is tough to gameplan for, no?

Nitpicking? You mean the game where LeBron was labeled a quitter?

http://bleacherreport.com/articles/527964-nba-heated-homecoming-celtics-vs-cavaliers-game-5-did-lebron-quit

I don’t know why you are falling all over yourselves because you upset Cols. You had to know what his predictable response would be, You spoke the truth on this one. And How cool is it he is villain and hero! It’s like a science fiction story in a comic book but it’s real. Amazing story for the Ages!

I think some of us just can’t resist arguing with him!

Ha Ha I see the genius and madness simultaneously .

This is one of the best blog posts ever at CtB. Great job on explaining how a city, a team and a player can represent a region’s collective psyche and embody something tangibly meaningful. There really was no other choice for the #1 Cavs villain than Miami LeBron.

That may be true, but if I was doing it, after #2 I would have said something like “our #1 villain has disappeared”.

Also, what is the point of a villains list, except for the fun of saying “Boo”, “Hiss”, etc.? In this case, everyone is having fun reminiscing about what jerks they were. Then you get to the end, and its “Surprize! It’s someone you like”. That is similar to watching a movie, and all the sudden something totally weird is put in for no reason but shock the watchers. Not one of your favorite movies.

I still boo and hiss every time I see LeBron in a Heat jersey…

Seeing him wearing #6 makes my stomach drop every time. Also, a lot of media folks like to say his best years are behind him as he spent his prime in Miami. And I hate that.

Our writers felt strongly enough to vote on it the way they did. I’m not going to short them by changing the rules or results after everyone had put the work in to vote on it all. We didn’t do any of this to shock anyone. We voted and followed where those votes went.

You tried to be clever and failed.

Give it a rest. Objectively, LeBron Raymone James incited more heartbreak, vitriol, and damage within the Cavs franchise and fanbase in four years than any other individual in history.

There is nothing to argue.

Re-watch that Heat @ Cavs game from 12/2/10 and tell me that anyone has been more hated by this fanbase than that man.

Just because LeBron is back in Cleveland now doesn’t mean his Miami incarnation was any less of a villain. MJ has been retired for 12 years and no one has a problem with him being on the list.

That’s rich Cols. If anyone on this site knows trying to be clever and failing, its definitely you.

I often consider your annoyance a success. Also, I might consider your arguments valid if you hadn’t given your opinion before the article was even published. It’s clear your mind was made up before you read it – if you read it.

Of course my mind was made up. There is no excuse for putting LeBron number 1, except you guys wanted to do something click baity and clever.

LeBron James himself would acknowledge that he was seen as the biggest Cavs villain when he left… he even claimed to embrace the villain role…

http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/commentary/news/story?page=jackson/110113

Why is this so hard for you to comprehend?

Hey Cols, so why, in your opinion, is LeBron NOT #1? You haven’t said why. You’ve just posted click-baity comments about how clever everyone thinks they are.

I have seen argument after argument that shuts down your assertions in this comment section, yet not a single piece of respectable rebuttal from you. So again, I ask as you continue to put down everyone on this blog, HOW IS MIAMI LEBRON >NOT< THE #1 CAVS VILLAIN OF ALL TIME?

That’s easy. Because LeBron left the Cavs and went to play in Miami with his best friends. By doing so he was able to get out of a very poorly run organization and go to somewhere nice, where fans wouldn’t call him a faliure and write stupid books about him (I’m looking at you Raab) in order to cash in on LeBron James. Also a place where he had an actual functioning top two or three GM instead of maybe the worst GM in all of basketball. By doing so, he did nothing to Cleveland. He never talked bad about… Read more »

Ok Cols. I might disagree with your stance but that’s all I wanted, an elaboration instead of repeated comments that some might find offensive. For what it’s worth (hyperbole alert), no fanbase has ever worshiped an athlete the way Cleveland did in the first LeBron stint, so we are the last people anyone should blame when it comes to the reason(s) he left. That’s why it hurt so much when he did, cuz we thought we had a special bond that went beyond athlete-fan (as explained in the blog post). Also, you can point the fingers at a hundred different… Read more »

This is one of my favorite articles. So there. Its not shocking if you take three seconds to think about it.

Thanks for the compliment!

Thanks a lot. I will note that much of my section was quoted from Tom and LeBron James himself. I stood on the shoulders of giants.

Very well written as usual. This entire website just continues to get better, and it was already good.

You should do a top 25 Cavs heroes next. Unless I missed that piece.

There was a #CavsRank during the 13-14 season (done in conjunction with other Cavalier blogs) that ranked the top 25 Cavs of all time. If you click on the #CavsRank category in the archives on the masthead, you can read all about them…

GREAT JOB ( AS USUAL ) GUYS——IF LEBRON NEVER RETURNS HOME HE WOULD BE IMMORTALIZED / CRUCIFIED FOREVER AS CLEVELANDS # 1 VILLAIN —–BUT HE DID DECIDE TO RETURN HOME A MUCH BETTER / MATURE PERSON / PLAYER WHO I AM ENJOYING MORE THAN ” BEFORE THE DECISION ” BOTH ON AND OFF THE COURT—-CAN WE EVER FORGET THE DECISION —NO !!!—-BUT WE CAN FORGIVE AND MOVE ON !!!——WHEN ( NOT IF ) LEBRON WINS HIS 1ST NBA CHAMPIONSHIP HERE ” IN THE LAND” IT WILL MEAN SO MUCH MORE TO HIM THAN THOSE IN MIAMI AND YOU WILL SEE… Read more »

Agree with NOMAD. In my case, I was in total shock for about a week. My girlfriend asked me if I would ever talk about basketball again. Then I was pissed for a year. But the fact is that the Cavs never put a good team around him. They could have won with a little luck, but not like now, where a team needs astounding luck to beat the Cavs. After a year I realized there was a real good chance LeBron would be coming back: KI + TT, Miami looking old, restoration of his image, etc. The only really… Read more »

I’m a LeBron fan, and have been since he was in high school. So I just follow his career wherever he goes. I was mad at first when he left and how he did it, but I eventually got over it like halfway through his first season in Miami. I live in Nebraska so I don’t have loyalty to franchises, I have loyalty to players.

Even the GOAT is not perfect! I think we are soooooo happy he was courageous enough to come back and take care of important unfinished business.

I agree completely that he is number on on this list. I’m still mad at him and not ashamed to admit it. Who gave us a worse four years than Lebron? Certainly not MJ, who we could at least compete against. LBJ was rubbed in our faces for four straight years and there was nothing we could do about. We sucked every year, he was in the finals, and it continually fed into the Cleveland sucks narrative the media adores. He became the player in Miamie we begged him to be while he was here. he teamed up with Wade… Read more »

Sweet. I have no problem whatsoever with him leaving an awful Cleveland team saddled with terrible players and a terrible coach because Ferrry was the worst GM you could imagine.

He got to play with his best friends in a way more cool and fun city for maybe the best GM ever in Pat Riley. It was a smart and great move by him.

More power to him, IMO.

Maybe you should root for the Heat if you feel that way.

Cols, I don’t know if you’ve ever been asked this, but what exactly is your connection to your Cavs fandom? It seems like it begins and ends with LeBron James. Have you ever lived in Cleveland? Or even Northeast Ohio? Through comments you’ve made, you’re clearly not a fan of any other Cleveland based team either. We all know you currently reside in Colorado, but I’m genuinely curious as to where your POV on LeBron and the Cavs is rooted. I mean, I live in LA now (and have since 1997), but I grew up just outside of Akron and… Read more »

You nailed it! He’s an embarrassment..

Quit picking on Cols, you guys (not that he wouldn’t piss off the pope). If someone shows up and is a Cavs fan, it does not matter where they are from.

I’m not picking on Cols. On the contrary, I’d just like to understand where he’s coming from. Cols has consistently been selective in his fandom towards the Cavs in the past, and it just seems like he’s more of a LeBron fan than a Cavs fan. And that’s okay, but at least that would jive with him being upset about LeBron being number one, and why he’d call the writers of this blog dumb and lame for voting as such…

Grew up in Youngstown. Cabs fan my whole life. I just didn’t get all bent because Lebrun chose to go play elsewhere considering what ferry put him through.

Check the blog. I’ve been here for a while. Even in the dark dark days of the dion draft.

Glad to hear that you’ve got some Ohio roots and that you’ve been a longtime Cavs fan. However, you’d be one of the few that didn’t get bent at LeBron for leaving. I’d say you are in a very small minority on that front. And I know you’ve been here for a while, it just seems that most of your praise is focused on LeBron. He still left the team you’ve rooted for your whole life, and did it in a pretty villainous manner. There is no denying that. If he had not returned, then the name in the headline… Read more »

HAHA… what’s ironic for me is that two of my good friends who are Cavs’ fans… grew up in OH and all that, they thought LBJ made the right decision leaving as well. I was the only one of us three who disagreed with the move.

Both agreed with Cols’ reasoning… why stay with an organization which was run so poorly (at the time)? I was super mad at the time the decision happened… but now, I am more understanding of it… kinda strange when I think about it.

Beautiful piece guys, both of you. Seriously. Really good stuff. Any writing from this blog that not only makes me love the CAVS and the CAVS players more, but makes me more treasure where I come from is just fabulous.

Really, you’ve represented not only the CAVS, but the city of Cleveland well here. Well done.

Thanks! That means a lot.

Is that Will Smith or Robert Horry?

http://www.cbssports.com/nba/eye-on-basketball/25296203/is-tristan-thompson-a-necessity-for-the-cavaliers-or-a-luxury?FTAG=YHF7e3228e

Interesting take on TT… what I found most surprising is the statistical information.

I wish the Cavs could trade TT for Ed Davis. He’s 90% of the player TT is at 40% of the price.

Why would they do that? They will just sign him and get 100% of the player. They will have zero cap space either way. The goal is to win the title, not win the title with the lowest payroll.

Except they are probably going to have the highest payroll in the history of the NBA.

Actually, I was wrong. Statistically, he’s pretty much Tristan’s equal, except Davis is a better shot-blocker. Non-statistically, I don’t know if he switches on pick-and-roll like TT. I doubt it.

I like Ed Davis… super-athletic guy, wasn’t he a free agent this summer? Thought he signed for a reasonable amount too. Davis hasn’t had nearly the PT Double T has, so Davis is probably under-developed that way. But in my opinion… paying TT anything over the 4/67m that JV of Toronto received would be a bad basketball and bad business decision. Honestly, someone mentioned in a prior thread that the most reasonable deal for TT is 3/36m. He gets paid a little now, and still becomes a free agent when the cap explodes. To me, TT is worth 10-12m and… Read more »

You are right, but of course we’re going to have to massively overpay for him because of our unique situation with the cap and inability to sign free agents. But I think everyone will agree its an overpay. On the one hand, I don’t think Toronto, or anyone else, will give him 90 million for five years like he wants. On the other hand, if we let him play for the QO and then he gets 4 at 70 mill from someone, all we have to show for it is the smugness of being right. We still won’t have the… Read more »

Also, Toronto can’t give him max money without giving up Demar Derozan and Terrence Ross…

@Joey B… great post all around, I definitely agree. Some really good points re: Cavs’ lack of options and the Shump comparison.

@EG, another good point. That would be a big sacrifice, although TT would complement JV well. Still… too much to give up it would appear.

I was day dreaming about a three way trade between the Cavs, Raptors and Hornets that would send Tristan to Toronto, MKG to the Cavs and DeRozen to the Hornets. MKG on that contract is a bargain. Love, LeBron and Kyrie’s outside shooting would offset his cross face chicken wing jumper.

No. TT>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>MKG

We do not need to have a low payroll. All that matters is a title.

That’s interesting – MKG is a great fit for us, but Thompson is too much to give up, probably.

That’s very intriguing to me… I disagree with Cols, I think MKG would be very comparable to TT; and MKG, like TT, are on the ascent with their games and youth.

It’s good that you titled this “the Miami LeBron,” because otherwise he shouldn’t be in these rankings.

Did anyone put the Spurs in this ranking. They are the ‘silent but deadly’ fart to the Cavs.

No. They only played heads up in 2007 in the playoffs. The potential for a rematch is there, though.

@IAmDPick: Israel, I’ve been told, do NOT want to clash vs Turkey. Too big, too strong, too Cedi Osman.

Phooey! Cols needed a triple pot brownie. Those things are expensive! You guys are driving Cols to the poor house.

They are not expensive.

Cols makes his own brah…

This is dumb beyond belief. OMG WHAT DOES IT MEAN!!!!!!!!!!!>!>!>!?!@#$!@#$<@#:$JJJJJJJJ%&*)#$G%&*#$H

CtSHARKJUMP

Serenity now.

I wonder if you even read these things.

Probably not, but he should. Great piece guys! Being the greatest hero, the greatest villain and then the greatest hero once again is a lot for one lifetime, let alone the first 12 years of an NBA career. Not to get overly religious, but (in keeping with Tom’s rhetoric from his writeups about the Decision), LeBron has been a Christ-like savior, a Judas Iscariot-level betrayer, and finally a Prodigal Son returning to his Northeastern Ohio kingdom. In Hollywood, we’re constantly on the lookout for amazing stories of heroes and villains, and the most compelling are always the ones about heroes… Read more »

Testified. People lose sight that sports is a subterfuge. It’s a story for us to occupy our time while we compartmentalize our own problems. Each season is a chapter in an anthology series, and LeBron has penned the tale of the Cavs and the NBA for the past decade. His heel turn and baby face turn back, makes his story so much more interesting than Jordan’s ever was.

Yeah, how stupid could you guys be? He’s the best player ever on the CAVS! We’re not good without him! We had the worst records without him!

We were awesome with him! Then he shocked the world and left! How does that make him a villain!?!

Oh, the sarcasm hurts my tummy.

LeBron James is the G.O.A.T. That is all.