Personality Crisis

2013-12-04

In almost any explanation of an NBA team’s relative success or failure, a disproportionately large amount of credit is given to one thing: culture. When a team wins, it has a culture that holds players accountable, that allows the young guys to grow and contribute to the team the right way, that demands that the game (and the game’s in-time proxy, the head coach) are respected. Long time guys stay because the culture is so good. New guys transition in well, often showing improvement or an unselfishness that was less evident in their previous stop, because the culture allows — and often demands — that they be a different player, a better player. The Spurs, the Bulls, the Heat and, until this season, the Celtics are all teams that don’t just beat you with the final score, they beat you in every aspect of their organizations … or so it is spun, anyway.

Likewise, when a team is down, the reasons it often stays down for a long time are not just talent and ability. Again, it’s about the culture. The culture of losing. Once-successful teams fear the deterioration of their culture into one driven by selfishness that operates at even half speed only half the time. Teams whose recent track record already has a giant, red L stamped on its culture card turn to changes in ownership, coaching, bringing in veterans who are viewed as “winners,” anything to break-up the losing mentality that has, the thinking goes, sunk itself so deeply into the organization that, as with a zombie-bitten hand, whole arms must be chopped off to keep the infection from spreading.

There is a truth to culture, but not a whole truth.

Sometimes a team’s orbit depends less on the construction of its ship than on some centralizing gravitational pull. Sometimes a team’s identity is not informed by some carefully laid out process, but by one individual. For better or worse, sometimes an entire NBA team can end up seeming like an extension of one of its players. Kevin Garnett, for example, is credited for the Celtics group-hug embrace of KG’s own feisty, defensive identity that helped turn that team from a loser into a champion. Just last week, Carmelo Anthony attributed many of the Knicks’ early-season struggles to not having Jason Kidd, despite Kidd’s actual on-court play being relatively inconsequential to their winning 54 games a year ago.

And for most every bad team — in fact, especially for bad teams — there is some unhappy, sulking borderline all-star who seems to bring the rest of the team down to his level. Fairly or not, DeMarcus Cousins has been viewed this way on a series of bad Kings teams.

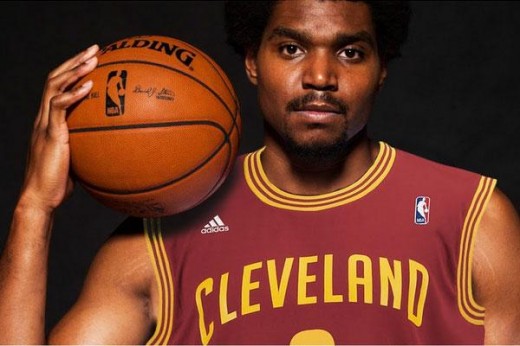

So far this season, despite a near abuse of the words “culture” and “process” in Mike Brown’s renewed jog with the team, the Cavs seem more like a DeMarcus Cousins Kings team than a culture team. Right now, their identity is a cult of personality… and that personality is the Rubix Cube that is Andrew Bynum.

Remember, this is the same Bynum who, less than a month ago, talked about continuing to contemplate retirement because “It’s tough to enjoy the game because of how limited I am physically.” That lack of enjoyment, understandable as it may be, has continually been on display this season. Bynum has looked tasked at being on the court, rather than relieved to be able to play the game that continues to earn him a fine livelihood. And, really, who can blame him? This is a 25-year old man having to deal with knees that still hurt when he plays, a body that is betraying him even though it should be much too young to do so. Bynum has been described as an intellectual guy and every deep thinker I’ve ever known when forced to think too long about his/her own potentially innate weaknesses… well, let’s just say things can get a little dark.

Remember, this is the same Bynum who, less than a month ago, talked about continuing to contemplate retirement because “It’s tough to enjoy the game because of how limited I am physically.” That lack of enjoyment, understandable as it may be, has continually been on display this season. Bynum has looked tasked at being on the court, rather than relieved to be able to play the game that continues to earn him a fine livelihood. And, really, who can blame him? This is a 25-year old man having to deal with knees that still hurt when he plays, a body that is betraying him even though it should be much too young to do so. Bynum has been described as an intellectual guy and every deep thinker I’ve ever known when forced to think too long about his/her own potentially innate weaknesses… well, let’s just say things can get a little dark.

More to the point, though, is that Bynum’s body coupled with his year away from the game has meant that he hasn’t been as good at being a professional basketball player as he once was. Look, his hangdog expression often says, this isn’t the player I want to be.

While, at this stage in his recovery, this sentiment makes perfect sense coming from Bynum, the more troubling thing is how much this expression, this body language, this sentiment appears to be shared by other Cavs players. What happens when the player all of your other young guys seem to be looking to and, in ways, patterning themselves after is himself a young guy who happens to be going through some stuff?

You get this:

Kyrie Irving: An inefficient volume scorer who has struggled to make his teammates better? Look, this isn’t the player I want to be.

Dion Waiters: A sixth man who struggles to move without the ball in a starter’s role while allegedly being frozen out of “buddy ball”? Look, this isn’t the player I want to be.

Tristan Thompson: An up-and-down performer still only showing flashes of being a consistent double-double threat? Look, this is… well, some of the time this is that player I want to be … totally … other times, not so much.

Anthony Bennett: [nothing is said … a single tear falls]

Right now, not only are the Cavs not playing good basketball, they look horribly depressed to not be playing good basketball — and while you prefer frustration and disappointment to the greatest indicator of losing culture, apathy, there is a degree to which the team, from an identity standpoint, if not always from an individual standpoint, has to show improved toughness. They can’t all be Andrew Bynum. I’m sorry. They just can’t.

Final note: Most of this article was conceived before the Cavs’ 97-93 win over the Bulls on Saturday night in which Bynum was a revelation to the tune of 20/10/5/3. Bynum fed off an early first quarter slam (“It was actually good to jump,” he said after the game “and to see it wasn’t too bad of a landing.”) and broke out a wide smile that he rode through his season-high 30 minutes. The rest of the Cavs were quick to share the spring in Bynum’s step and the Cavs played arguably their most complete game of the season. I don’t see how that should change my point here, though. If Bynum is going to be having fun and smiling, he’s probably being successful. If he’s successful, he’s a game-changer and this team’s probably winning. If this team’s winning, many warts will be covered up. My main point — finding that your team’s identity is tied to the up-and-down moods of a player with Bynum’s collection of reasons to be up and down is not super encouraging — remains.

Bynum is fine. I see him laughing on the bench and even jawing on the court and he cracked a smile against chicago and i know he had to feel good after that game by his tone last night. What does concern me is Dion Waiters’ attitude. He’s an easy target I realize because of the whole team meeting thing, but in a time out you could see yesterday his body language was so poor. What i did like was Kyrie on the bench in the same shot next to him clapping with a come on guys demeanor, (if anyone… Read more »

Jason Kidd has had more off the court issues than the 12 players on this team.

I saw an “identity” tonight against Denver. Ball movement, defensive intensity, and pushing the ball up the court. Just keep that up and we’ll be fine.

Enjoyed the T Thompson – Fareid match up.

Is it Bynums fault that the Cavs were bad before Lebron? Is it his fault Lebron left? Didn’t realize Bynum was on the team last year when the Cavs won 24 games.

But go ahead, blame it on the new guy for an organizations losing culture.

I was being sarcastic scotch. The Pistons won the title the year they had one of the worst draft picks in NBA history.

Anthony Bennetts lack of production thus far has zero impact on the Cavs team culture. Nor does the number of people the Cavs interviewed for their coaching vacancy.

The pistons culture was on the way out before that pick happened. Culture is not so much about whether everything goes correctly, culture is about buy-in. You get rid of guys that don’t buy in, you make sure everyone you bring to the culture does buy in or they also get the boot. When Nelson helped the Stephen Jackson and Baron Davis led Warriors beat a clearly superior mavericks team, the deal was that players bought into Nelson semi-madness. Van Gundy’s success with Dwight Howard and a bunch of three point shooters was about total buy in to his defensive… Read more »

Yes, Nate, clearly a big part of the problem with the Cavs culture is that their number one pick in a terrible draft has been bad in limited minutes.

I mean all you have to do is look at the Detroit Pistons to see what happens to a teams culture in these situations. After they spent the number two pick in maybe the best draft ever on a complete bust their team culture was GONE.

Trade for Luke. Trade for Cody. Reunite the Zeller brothers. We have our own Big 3. Bam, all problems solved.

There’s no goofy white guy named “Luke” on the team this year. That’s the problem. Luke Zeller is available. Just saying.

@ Demetrius- Terry wasn’t a nominal “starter” but he was 2nd on the team in mins played and 3rd in mpg for the season. He was also good enough to start in the NBA for 7-8 years of his career before moving to the bench. Most of the top 6th men in the league (all?) were good enough to be starters. Jamal Crawford has 4 seasons playing over 37 mpg in his career. If Dion “isn’t good enough to start” then he isn’t good enough to be an impact 6th man.

It’s hard to ‘peg’ what the Cavs culture is or which player(s) are shaping it. With the exception of Dion (due to some ‘issues’ at Syracuse), all of the recently drafted guys are/were considered to have very good character. Andy, our longest standig Cav is also considered a high character, hard working – energy guy. It seems that the only guy on the roster that really has questionable character is Bynum. And honestly, Bynum seems to be doing everything right from his pre-season workouts and focus at the Cleveland Clinic to his on-court efforts including his honesty about his physical… Read more »

I have always been struck by theunderstated importance of “continuity” in establishing a definable personality/culture for an organization like the Cavs. Then I reflect on the number of changes that have been made over the past 12 months i.e. over 50% of the team is new, 5 of the new players are rookies, the overall roster is one of the youngest in the NBA, a new coaching staff has been put in place, and the overall team philosophy has been re-calibrated entirely. There is not a hint of continuity for the team to build on. Mike Brown clearly has his… Read more »

Well, let’s not sugarcoat the fact that the Spurs, Bulls, Heat, and past Celtics teams all made consistently good decisions. That’s part of culture. Part of the reason guys live with Pop’s coaching decisions and the Spurs management decisions: they’ve been uncannily good at making incredibly intelligent decisions: Tony Parker with the 28th pick of the draft, Manu Ginobili with the 57th, Tiago Splitter 28th. They traded George hill to get Kawhi Leonard 15th. Furthermore, you can juggle your line your lineup when you’re winning, which is what Pop does. Part of a “culture of winning” is because a team… Read more »

I enjoyed this. It’s interesting that there’s little to no mention of the coaching influence on culture and identity. A huge issue with observers has been Mike Brown’s constantly shifting rotation and minute allotment and how that affects his players. Interestingly enough, one of the most fluid rotations in the NBA belongs to Brown’s philosophical mentor in San Antonio. It seems that the issue here though is the lack of trust and institutional support here. If Pop jerks around Nando De Colo or moves Tiago in and out of the starting 5 it’s assumed that there’s a real strategic reasoning… Read more »